Major Questions: The Supreme Court and the Decline of Textualism

At the end of its most recent and controversial term, the Supreme Court handed down a decision against the Environmental Protection Agency’s efforts to regulate greenhouse gas emissions under the Clean Air Act (West Virginia v. EPA, 142 S. Ct. 2587 (2022); Slip Opinion, Docket 20-1530). The Court majority announced what it called the “major questions doctrine” which effectively created an exception to its statutory interpretation method known as textualism. The decision raises major questions in its own right, including whether this exception threatens to swallow the rules of textualism. This article provides an initial review of the Supreme Court’s opinion and the dissent, adding to an earlier discussion of the case (farmdoc daily, April 7, 2022).

Background

As discussed previously, textualism is a judicially created method for interpreting and applying statutes that is largely credited to the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. It works from the premise that only the actual words of legislative text were voted on by Congress, thus only the words of the text were enacted into law. Accordingly, the words of a statute are to be interpreted or understood in their ordinary, everyday meaning (unless technical) and they should be given the meaning the words had at the time the text was enacted (farmdoc daily, April 7, 2022). In 1989, former Justice Kennedy explained that “statutory language cannot be construed in a vacuum” and that it was a “fundamental canon of statutory construction that the words of a statute must be read in their context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme” (Davis v. Mich. Dept. of the Treasury, 489 U.S. 803, 809 (1989)). The majority opinion in the West Virginia case also quotes this fundamental canon (West Virginia, Slip Op., at 16).

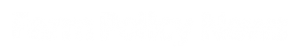

The statutory text at issue in the West Virginia case is contained in Section 111 of the Clean Air Act, “Standards of performance for new stationary sources” (42 U.S.C. §74111). That section resides in Title 42 (The Public Health and Welfare), Chapter 85 (Air Pollution Prevention and Control). Figure 1 highlights the provision in the overall statutory system between the “State implementation plans for national primary and secondary ambient air quality standards” (NAAQS) and the provision for “Hazardous air pollutants” (HAP) (42 U.S.C. §7410 and §7412 (respectively)). These are the three provisions authorizing EPA to regulate air pollution.

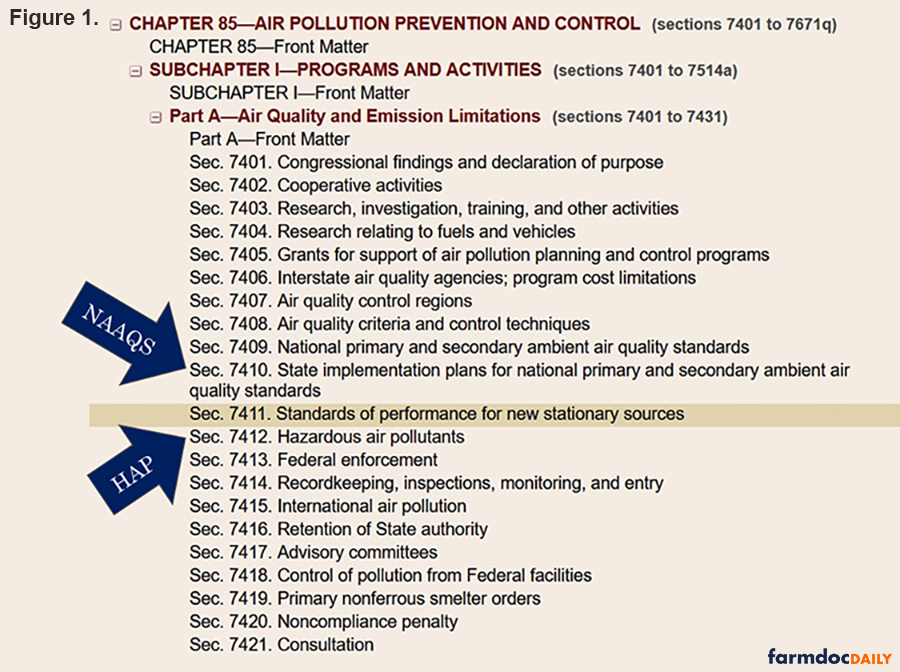

At issue before the Court was the extent of EPA’s authority to establish a “best system of emission reduction” as the standard of performance for stationary sources of greenhouse gases contributing to climate change (42 U.S.C. §7411(a) and (d)). The Clean Air Act is relatively clear: EPA “shall prescribe regulations” for establishing “standards of performance” applicable to existing sources as it “would apply if such existing source were a new source” (42 U.S.C. §7411(d)(1)). Congress defined the term standard of performance as one “which reflects the degree of emission limitation achievable through the application of the best system of emission reduction” (BSER), taking into account the costs and any non-air quality healthy and environmental impacts, as well as energy requirements (42 U.S.C. §7411(a)(1)). Figure 2 provides the relevant statutory provisions (emphasis added).

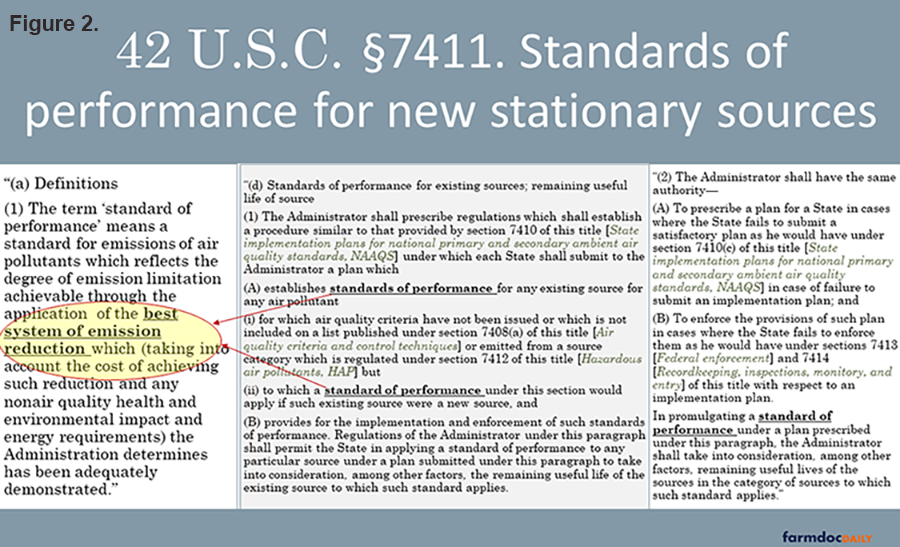

The Clean Air Act as it exists today is largely the product of three Congressional enactments amending the statute in 1970 (P.L. 91-604), 1977 (P.L. 95-95) and in 1990 (P.L. 101-549). Each of these amendments to the statute specifically revised the definition for standard of performance under which Section 111 regulation operates. Figure 3 summarizes those definitional revisions. The 1990 amendments constitute the current definition in the statute (red text represents new text; emphasis added). Important for statutory construction and understanding the intent of Congress, note how the 1990 amendments struck the highlighted phrase from the 1977 amendments which applied the best system to “that source.” In the simplest of terms, this indicates that Congress struck the requirement that regulatory efforts are to be focused on the specific source of the pollution and broadened the authority for EPA to regulate under the best system.

Discussion

The question before the Supreme Court was the extent of the authority that the statute conferred on EPA to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. The Obama Administration EPA in 2015 created a three-part plan known as the Clean Power Plan summarized as follows: (1) improved heat rates or methods for burning coal more efficiently; (2) shift from coal to natural gas; and (3) shifting from coal and natural gas to renewable sources or zero-carbon sources, such as wind and solar. The second and third methods were applied at the level of the electricity grid and are the source of the objections raised by West Virginia and other states. The shifting was system-wide, not concentrated at the source of the pollution (i.e., the power plant). The system-wide or grid approach permitted sources some flexibility to find efficiencies, including through trading credits (West Virginia, slip op., at 8). The Supreme Court previously stayed the original Clean Power Plan in 2016 and the Trump Administration replaced it in 2019. The D.C. Court of Appeals rejected the 2019 rule. The Clean Power Plan, however, never became operational and the Biden Administration informed the courts it would begin new rulemaking rather than attempt to revive the 2015 rule. This raises procedural and jurisdictional concerns about the Supreme Court even hearing this case.

As an initial matter, the Court majority concluded that the appellate decision reinstated the 2015 rule and threatened to harm the plaintiffs. Chief Justice Roberts wrote the majority opinion. He was joined by Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch (who also filed a concurring opinion that Justice Alito joined), Kavanaugh, and Barrett. These are the six ideologically conservative justices appointed by Republican Presidents, including the three by President Trump. The dissent was written by Justice Elena Kagan and it was joined by Justices Breyer (who retired at the end of the term) and Sotomayor. The dissenting justices are the liberal wing of the Court and were appointed by Democratic Presidents. On the jurisdictional issue, the dissent argued that the majority issued “what is really an advisory opinion on the proper scope of the new rule EPA is considering” which violates the Constitutional requirement that the Supreme Court hears only cases and controversies (West Virginia, slip op., Kagan, dissenting, at 4). At the very least, this matter magnifies the oddities and questions for the majority’s decision.

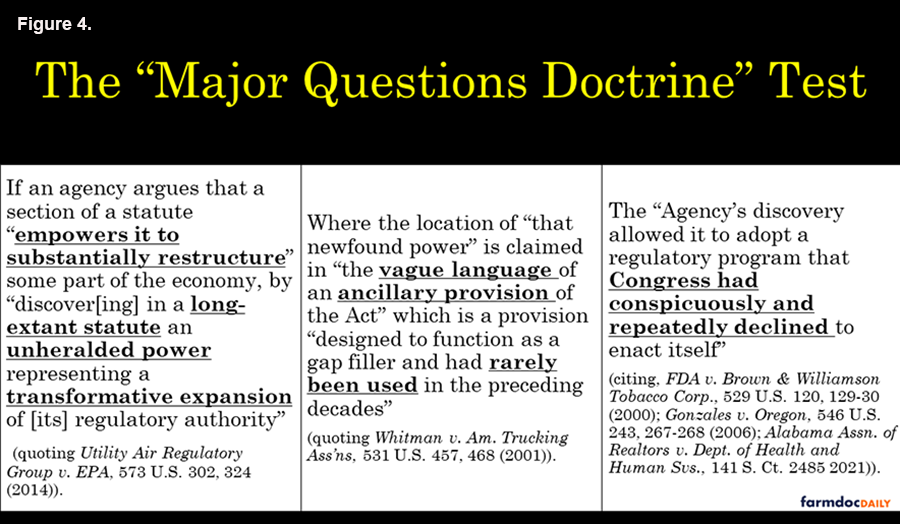

Procedural matters aside, the heart of the issue is the extent of EPA’s authority under Section 111. By any logical reading of the statute—let alone the strict reading typically deployed under the textualism framework—Congress authorized three basic regulatory efforts to combat air pollution, one of which was the standards of performance under Section 111. By its terms, that section covers pollution not otherwise regulated under the HAP and NAAQS provisions (42 U.S.C. §7411(d)(1). The majority decision does not analyze the statute under textualism principles or methods, nor does it deploy traditional canons of statutory interpretation. Instead, the majority announced what it called the “major questions doctrine” for statutory interpretation which operates as an exception to textualism. Specifically, “in certain extraordinary cases, both separation of powers principles and a practical understanding of legislative intent make us reluctant to read into ambiguous statutory text the delegation claimed to be lurking there.” In such cases, “something more than a merely plausible textual basis for the agency action is necessary” and that the “agency instead must point to clear congressional authorization for the power it claims” (West Virginia, slip op., at 19 (emphasis added; internal quotations and citations omitted). The majority created a three-part test for the application of the “major questions doctrine.” Figure 4 summarizes this test (emphasis added).

For matters of law and judicial interpretation of statutes, this “major questions doctrine” raises major questions. On its face, it is very arbitrary and extraordinarily subjective. For example, the majority fails to explain exactly what would constitute a substantial restructuring of the economy to trigger the doctrine. The majority also does not explain what should be considered an unheralded power or a transformative expansion of regulatory authority. Arguably most troubling is the rather thinly veiled disregard for and disrespect of statutes. To the majority, an unelected judge with a lifetime appointment can consider some statutory provisions as nothing more than vague text in ancillary provisions (presumably, auxiliary or supplementary, or subordinate), especially if long-extant (presumably long-existing or not destroyed or lost) and rarely used. In effect, the major questions doctrine instructs judges to pick-and-choose among statutory provisions to establish which provisions are superior to others.

The “major questions doctrine” is additionally confusing in the context of the West Virginia case. The provision to which the majority applied it (Section 7411(d)) is one of the three main methods for regulating air pollution by EPA. Moreover, a “standard of performance” is a term defined by Congress and, most importantly, it was redefined Congress to broaden its scope and application (see, figure 3). The doctrine announced and the test created do not appear applicable to the provision being reviewed. Confusion turns to concern, however, when the majority opinion refers to Section 111 as a “previously little-used backwater” of the statute. This is not a legal conclusion, there is no legal categorization of statutory text as backwater; the law is presumably the law as contained in the text enacted by Congress, none of which is to be presumed by judges as inferior or surplusage. That had long been the argument of textualists. The backwater designation is, however, an important part of the majority’s justification for applying the “major questions doctrine” (West Virginia, slip op., at 26). It presents more than an exception; if this is to be the legal standard, then the “major question doctrine” effectively represents the decline and eventual end of textualism.

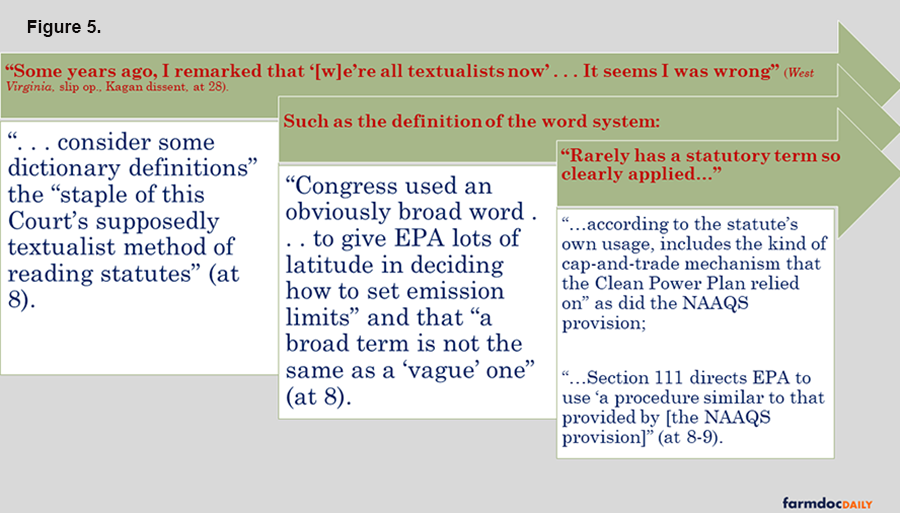

Not surprisingly, Justice Elena Kagan’s dissent is particularly pointed. She offers a strong refutation of nearly every aspect of the majority opinion. She argues that the majority “is textualist only when being so suits it” but if textualism “frustrate[s] broader goals, special canons like the ‘major questions doctrine’ magically appear as get-out-of-text-free cards” (West Virginia, slip op., Kagan dissent, at 28). By doing so, “the majority flouts the statutory text” (Id., at 12). At one point, she notes that “looking at the text of Section 111(d) might here come in handy” (Id., at 24). Figure 5 highlights additional points from the dissent.

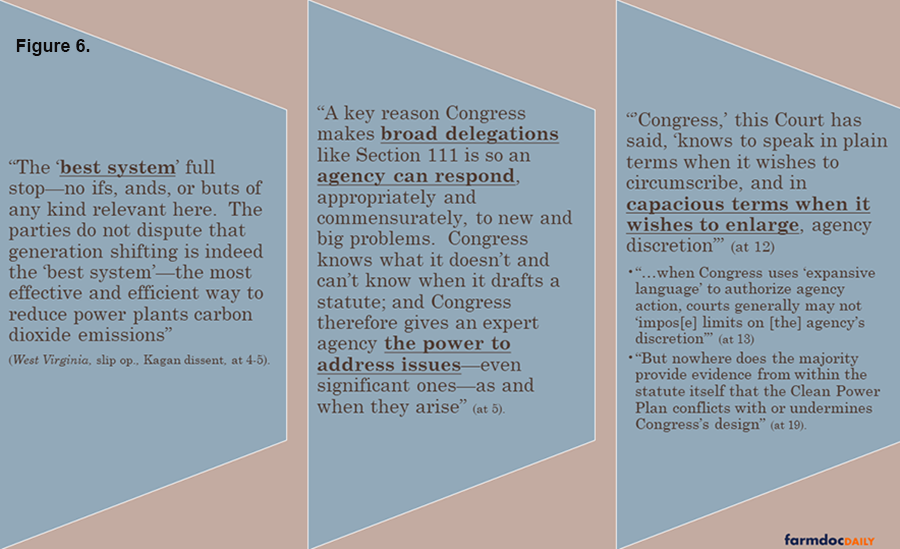

The problem for the majority, according to the dissent, is the obviously broad delegation that Congress provided to EPA for regulating air pollution in the statutory text. The “limits the majority now puts on EPA’s authority fly in the face of the statute Congress wrote . . . when it broadly authorized EPA in Section 111 to select the ‘best system of emission reduction’ for power plants” (West Virginia, slip op., Kagan dissent, at 4-5). Figure 6 highlights further arguments on this broad delegation by the dissent (emphasis added).

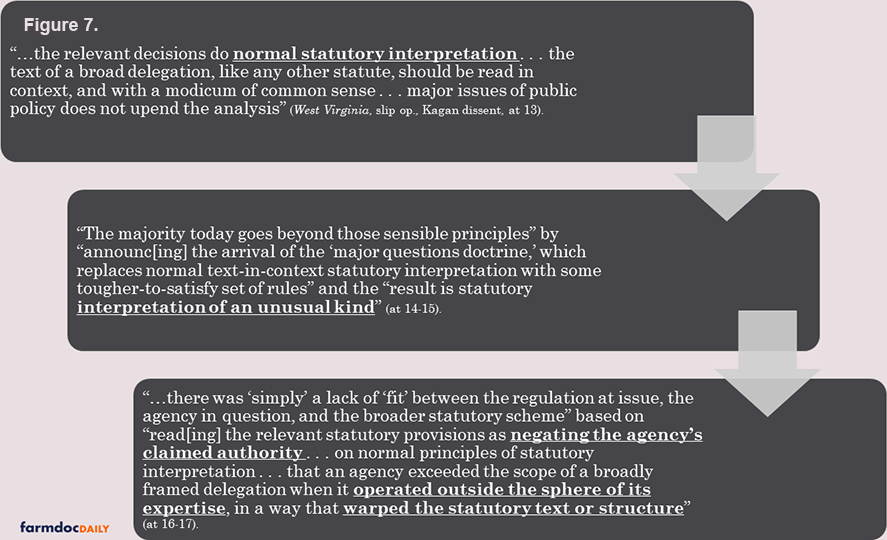

As for the newly announced “major questions doctrine” the dissent argues that it is not an actual method of interpretation and that it did not exist prior to the decision. The “majority claims it is just following precedent, but that is not so” because the “Court has never even used the term ‘major questions doctrine before’” and, most importantly, “in the relevant cases, the Court has done statutory construction of a familiar sort” (West Virginia, slip op., Kagan dissent, at 15). Rather than a “major questions doctrine,” the dissent argues, the cases the majority relies upon demonstrate “a consistent presence” of “something the Court found anomalous—looked at from Congress’ point of view—in a particular agency’s exercise of authority . . . the agency had strayed out of its lane, to an area where it had neither expertise nor experience” (Id., at 18-19). Figure 7 highlights further arguments by the dissent on this point.

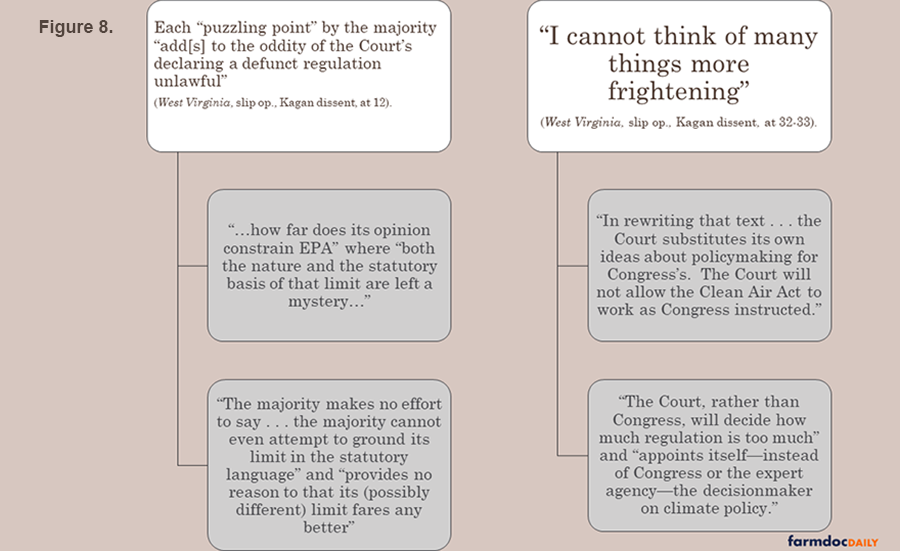

The final point by the dissent may be the most important, as well as the one with troubling historical precedent. Justice Kagan, in effect, is arguing that the majority has used this new “major questions doctrine” to usurp power, taking it from Congress and the Executive branches. This raises profound concerns about the judiciary grabbing power over important matters of policy from the elected branches of government vested with that power by the Constitution. The quotes in Figure 8 highlight this point further.

Concluding Thoughts

In total, the opinions in West Virginia v. EPA sound concerning echoes from the 1930s when reactionaries on the Supreme Court actively worked against the New Deal legislative and regulatory efforts to combat the Great Depression (Metzger, 2017). Among those cases was the Court’s controversial decision declaring the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 unconstitutional (U.S. v. Butler, 297 U.S. 1 (1936)). The dissent in that case called the majority decision “judicial fiat” and warned against “the mind accustomed to believe that it is the business of the courts to sit in judgment on the wisdom of legislative action” (U.S. v. Butler, 297 U.S., at 328-29 (Stone, dissenting)). The “major questions doctrine” announced by the new conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court raises anew these concerns from decades ago. Setting aside the politics of environmental regulation generally and climate change specifically, the decision is a striking exercise of judicial power. There is little to convincingly dissuade from concluding that what the decision actually announces is a new version of judicial fiat. If judges or an ideological faction of justices disfavor agency action, or the authority delegated by Congress to an agency, they are empowered to consider whether the statutory provision is somehow too minor or inferior—based on what exactly is entirely unclear. The Clean Air Act provision used to announce this doctrine begs the question. How is Section 7411 more of a backwater or more ancillary than Section 7410 (NAAQS) or 7412 (HAP)?

Without doubt, Agencies can misinterpret statutes, including efforts to expand their own authority, but the response to that begins with Congress and the many tools at its disposal. A court’s role should, by constitutional necessity, be limited and constrained by a respect for the role of the political branches in policymaking. The “major questions doctrine” presents an absurdity. What minor questions are written into law by Congress? Is addressing air pollution one of them? What minor questions come before the Supreme Court of the United States? Textualism’s semantic gerrymanders, pedantic discursions, and dueling dictionary definitions were bad, but this is worse. The court has decoupled legal reasoning from statutory text and empowered judges to proclaim a matter too major for words they deem too minor. Whatever this doctrine is, it is not within the realm of the rule of law; it is rule by the prerogative of a judge or justices. It secures extraordinary power for the least democratic branch of government with vast implications for policy, legislation and the American system of self-government.

References

Metzger, Gillian E. “1930s Redux: The Administrative State Under Siege.” Harv. L. Rev. 131 (2017): 1.

Coppess, J. "Another Curious Case for the Supreme Court; A Test for Textualism." farmdoc daily (12):47, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 7, 2022.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.