Farm Bill 2023: The Intersection of Base Acres and Reference Prices

The debate about base acres and whether Congress should require a mandatory update in the 2023 Farm Bill can be lost to the oddities and obscurities of the policy, as well as the interests of political factions. Base acres are intended to avoid impacting farmer production and planting decisions; therefore, the program payments are the critical context because a mandatory base acre update only impacts payments. This article seeks to add context to the discussion by reviewing the intersection of base acres and reference prices.

Background on the Intersection of Base Acres and Reference Prices

Base acres have been established using an historic average of acres planted (or prevented from being planted) to crops covered by the programs and most of the major program crops have base acres that exceed historic averages planted to those crops. Moreover, recent averages of planted acres are less than average enrolled base acres, with soybeans the most notable exception (farmdoc daily, July 20, 2023; August 3, 2023). While some states could lose base acres, this reflects planting and land use decisions by farmers and landowners. A mandatory base acre update would be expected to end payments on land that has not been farmed in recent years and preclude payments for those acres even if they are brought back into production. A mandatory base acre update does not prevent acres from being farmed.

Most important for the policy debate is the fact that substantial base aces will shift from some covered commodities to others, with the biggest shifts to soybeans. Political opposition to a mandatory base acre update is largely fueled by interests that receive generous payments on base acres of crops that farmers have not been planting and where those acres would shift to crops with less generous payments. Underwriting these differences are the statutory reference prices Congress enacted in 2014 (P.L. 113-79) and continued in 2018, but with the addition of seed cotton and the inclusion of an escalator calculation (P.L. 115-334; farmdoc daily, February 14, 2018). The statutory reference prices for covered commodities are included in payment calculations for both Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) and Price Loss Coverage (PLC) programs, but with different impacts. Current statutory reference prices are found in the definitions section for commodity policy (7 U.S.C. §9011; see also, farmdoc daily, June 29, 2023).

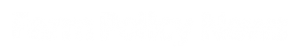

Statutory reference prices are most relevant when compared to the crop’s marketing year average (MYA) prices, because payments are triggered when MYA prices fall below the statutory reference price. Figure 1 compares the statutory reference prices for the major program crops (corn, soybeans, wheat, all rice, peanuts, and seed cotton) by calculating the statutory reference price as a percent of the MYA price each year from 2015 to 2021, and the projected MYA prices for 2022 through 2033 from the May 2023 CBO Baseline (CBO, May 2023).

The light gray area labeled “No Payment Zone” is when the statutory reference price is below 100% of the MYA, which means the MYA prices—the prices farmers received for the crop in the marketing year—are higher than the statutory reference price and therefore no payment would be expected from PLC. The disparities amongst these crops are obvious year after program year.

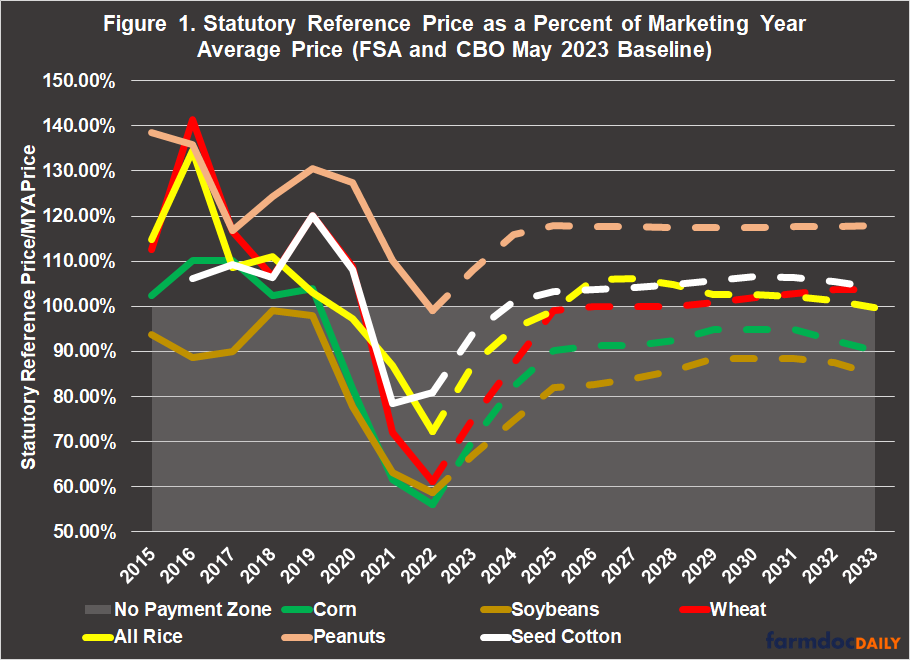

In addition to the statutory reference price, Congress added a calculation for an effective reference price (or an escalator) in the 2018 Farm Bill, defined as the higher of the effective or statutory reference price. The escalator for the effective reference price is calculated as 85% of the Olympic moving average of the most recent five crop years (excluding the highest and lowest years), but not to exceed 115% of the statutory reference price. This increases reference prices above the statutory level when there have been sufficient years of higher market prices for the crop and falls back to the statutory reference price when market prices decline over multiple years (see e.g., farmdoc daily, June 29, 2022; February 7, 2023). According to CBO price projections in the May 2023 Baseline, only corn, soybeans and wheat will have an effective reference price above the statutory reference price and only for a few years. Figure 2 illustrates the comparison between the effective reference prices and statutory reference prices for these three crops in the CBO May 2023 Baseline.

For seed cotton, rice and peanuts, the statutory reference prices enacted by Congress are too high for the escalator provision to change the effective reference price trigger, even with higher crop prices in recent years. This has multiple implications for a farm bill debate, not least of which for any update to base acres.

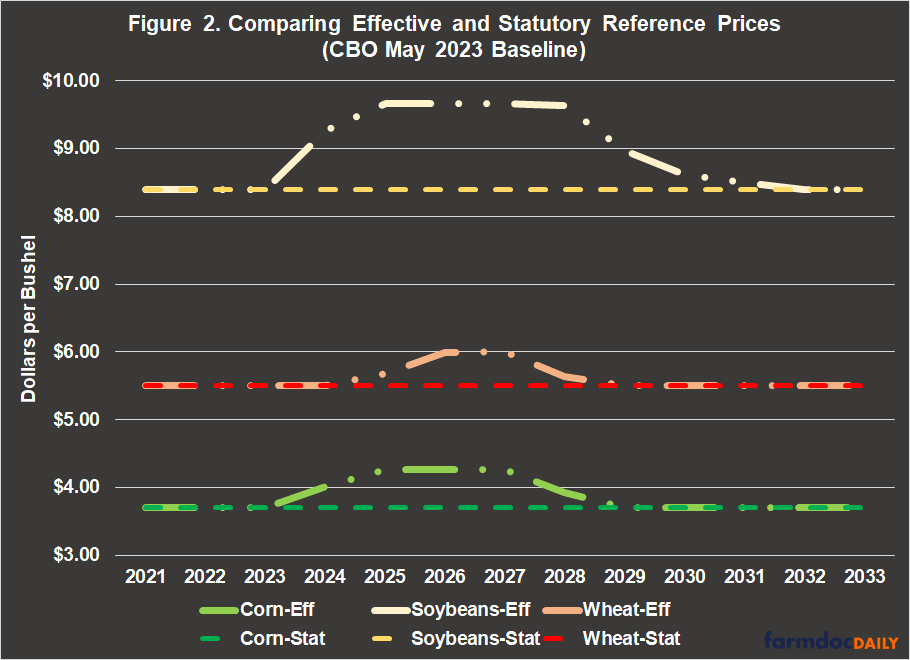

Discussion: Base Acre Bonus; A Thought Experiment at the Intersection

Five-year Olympic moving averages are largely determined by price movements in the market. The statutory reference prices, however, are purely political decisions by Congress. Figure 3 illustrates an estimated national average payment amount for the major program crops, calculated by multiplying the PLC payment rate by the national average payment yield as reported by USDA’s Farm Service Agency (FSA) for the most recent program years (2019 to 2021) (USDA-FSA, ARC/PLC Program Data). The actual payment amount for a farm will be the payment rate (any deficiency in MYA from the effective referenced price), multiplied by the farm’s program yield for the crop, and 85% of the farm’s base acres (defined as payment acres) for the crop. In Figure 3, the national average PLC yields are used to substitute for individual farm program yields.

Figure 3 clearly illustrates the disparities amongst these major program crops, most notably for peanuts. Simply put: if a farmer has peanut base acres, they have received large payments on those base acres each of the last three years and that farmer did not need to plant peanuts to get the payments.

To explore the implications of this intersection between reference prices and base acres, this discussion attempts a thought experiment using the 2019 PLC program payments. The thought experiment is as follows: what if the 2019 payments used the planted acres of each commodity rather than base acres? To be clear, this is not a policy proposal being discussed, nor is it likely; the thought experiment is an effort to illustrate that revising base acres, such as through a mandatory update, is not simply a matter of increasing or decreasing base acres of some crops. What matters is both the base acres and the reference prices.

Figure 4 provides an interactive map for this thought experiment. The amounts in Figure 4 were calculated using FSA data for base acres enrolled in PLC in 2019, acres planted, and payments. The amounts for each state and for the crops within that state equal the difference between the actual PLC payments for 2019 and an alternative PLC payment calculated by switching base acres with planted acres (keeping the same percentage of acres enrolled in PLC). In other words, instead of calculating payments on base acres, the planted acres for each crop were used as if those planted acres were what had been enrolled in PLC in 2019. Those states and crops with negative values are those in which the alternative (using planted acres) would have resulted in more PLC payments in 2019 than using base acres. Another way to look at the map is that the states and crops with positive values received a base acre bonus in that they received more in payments using base than they would have if planted acres were enrolled in PLC in 2019.

Figures 5a and 5b support the map in Figure 4. First, Figure 5a provides a chart for the base acre bonus calculation, comparing the actual PLC payments (enrolling base acres) to the alternative PLC payments (enrolling planted acres) by State and crop. Second, Figure 5b completes the thought experiment by comparing the base acres enrolled in PLC in 2019 to the alternative of planted acres enrolled in PLC in 2019 by state and crop.

The key takeaway from this thought experiment is that a mandatory base update is not simply a matter of acreage changes among the program crops. The impact depends on the payments made on those base acres, which is largely driven by the reference prices enacted by Congress. The biggest impact would be from peanut and rice base acres (high reference prices; large payments) to soybeans that received no payments. While some crops and states would have received less in PLC payments in 2019 if planted acres had been used, this is only a loss if the reverse is also accepted as true: those crops and states have been receiving a base acre bonus in terms of excess payments for crops not grown. If base acres were more closely aligned with planted acres, the state and crop impact would depend on the relationship between the reference price and market year average prices as well as the relationship between base acres and planted acres.

Concluding Thoughts

At the intersection of base acres and reference prices, each policy design complicates the other. A mandatory base update that better aligns program payments with planted acres will impact states and crops to different degrees depending on where Congress established reference prices relative to market prices. Moving program acres from crops with higher relative reference prices will reduce payments to those crops and states. Raising reference prices will also have significantly different impacts on states and crops that depend on the differences between base acres and planted acres. Making both changes at the same time complicates the issue further; under budget rules that would score the changes over 10 years, the impacts are magnified. Soybeans provide the primary example with a low reference price relative to market prices and low base acres relative to planted acres.

Whether any state or crop loses in this situation depends on the degree to which they have benefitted from the current policy designs. It is at this intersection that the political collisions within the farm coalition occur as farmers, commodity factions, and production regions are pitted against each other. Because of the existing disparities in reference prices amongst crops, and the existing differences between base acres and planted acres of those crops, those conflicts, disagreements, and challenges already exist. They have, in fact, existed for much of the policy’s history. Proposals such as a mandatory base update do not create those conflicts anew, they simply inherit them. The interests that have received the bonus previously see loss in any change that doesn’t continue or build upon the windfall.

References

Congressional Budget Office. “CBO’s May 2023 Baseline for Farm Programs.” https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-05/51317-2023-05-usda_0.pdf

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023 and Policy Design: Another View of ARC-CO and PLC." farmdoc daily (13):119, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 29, 2023.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023: Planted Acres and Additional Pieces of the Base Acres Puzzle." farmdoc daily (13):143, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 3, 2023.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023: Reviewing Pieces of the Base Acres Puzzle." farmdoc daily (13):134, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, July 20, 2023.

Coppess, J., N. Paulson, G. Schnitkey and C. Zulauf. "Farm Bill Round 1: Dairy, Cotton and the President’s Budget." farmdoc daily (8):25, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, February 14, 2018.

Schnitkey, G., C. Zulauf, N. Paulson and J. Baltz. "2023 and 2024 Effective Reference Prices and the Next Farm Bill." farmdoc daily (13):21, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, February 7, 2023.

USDA-FSA. ARC/PLC Program Data, accessed August 10, 2023. https://www.fsa.usda.gov/programs-and-services/arcplc_program/arcplc-program-data/index

Zulauf, C., G. Schnitkey, K. Swanson, N. Paulson and J. Coppess. "Effective Reference Price – Past and Future." farmdoc daily (12):97, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 29, 2022.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.